-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

I sat in the Director for Minority Achievement’s office as she advised a young senior at her desk.

“What’s the point anyway?” asked the senior of immigrant background. “I can’t go to college. I can’t work. There won’t be options for me.”

“I recommend staying in school one year longer. For one, school isn’t free after high school,” counseled the Director. “Also, it might give time for things to change…” A silent pause ensued.

“Tell me about the background of the teachers I’m speaking to,” I asked the Director as we walked down the hall, laughing students running past us.

“They’re all ESL teachers,” she said. “Our ESL students get left out of most extracurricular activities. For one, many of them can’t stay after school. Your program would have to be during their class. We want it to be the thing at this school that is for them.”

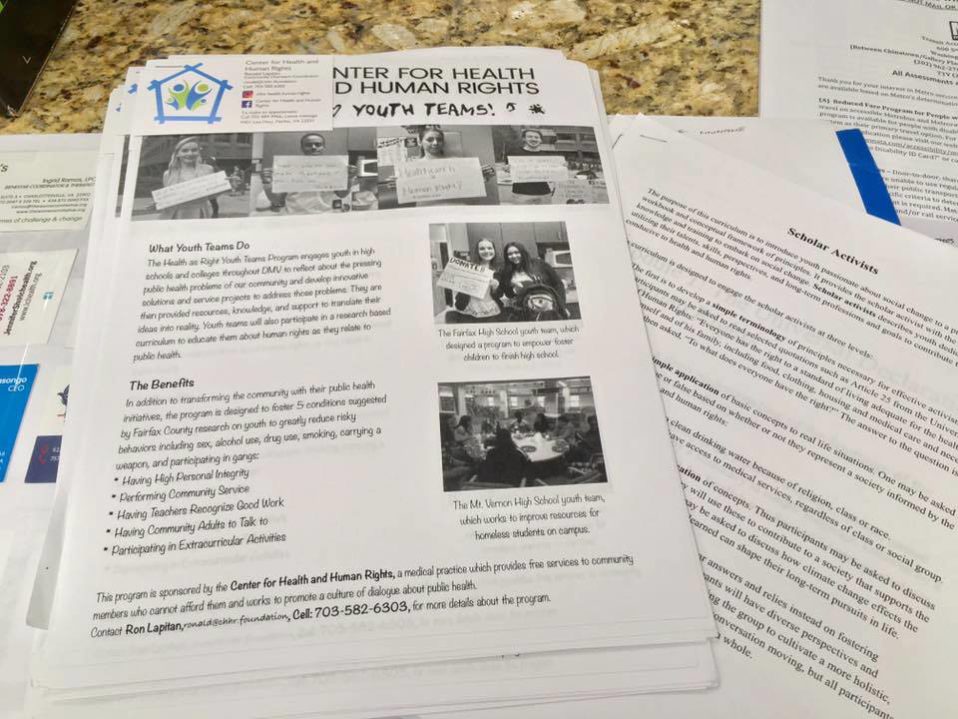

“If you had the power to change one thing about your community, that if it changed, it would cause people to live healthier and better lives, what would you change?” I asked the teachers of the meeting the first question I ask students in our program. “After our students brainstorm problems in the places where they live that they would be passionate about changing, our Center provides them resources to create service projects to translate their wishes into reality,” I described.

“This semester, I can teach books on the themes of justice and human rights to go along with your curriculum,” said the English teacher whose class will serve as the pilot for the in-class version of the Health as Right Program this semester.

“And if it empowers the students, we can expand it to the other ESL classes next semester. These students can be the ambassadors,” added the Director. Next week, I will attend the English teacher’s class every day to get a sense of how she teaches and how the students learn. Then we will consult on how to organically integrate our program into her lessons.

“See you next week!” said the English teacher excitedly. We shook hands and parted.

I walked out of the school, a background check application in hand now that I will be a regular presence, pausing to reflect and appreciating my smallness in the face of our charge. To make our youth stronger, by helping them discover in themselves those things which no one in this world can steal; their convictions about the value of human beings, their imagination of a different kind of world, and their sense of possibility that they can create that world through service to humanity. To give them permission to express these treasures folded inside them in layers of uncertainty and fear, to normalize them until they become a culture.

I am not worthy to be the one to shape a young person’s mind. But I am here, so I’ll do my best. Friends on their way to their next classes laugh as I walk through the hallway, full of dreams and a sense of possibility about the way the world can be. My dreams for the future are wrapped up in these young people.

“Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better, it’s not.”

-Yorktown student art in the hallway

#healthasright #youthteams

-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

Today, the Center for Health and Human Rights traveled to one of the schools in our program to do free sports physicals so the students could enroll in sports. The student body of the International High School in Langley Park in Maryland is 100% immigrants and refugees, most of whom are without insurance. “A sports physical costs $80-$100,” commented Dr. Milani as we drove to the school. In all, we saw about twenty students, about $2,000 in free services.

Today, the Center for Health and Human Rights traveled to one of the schools in our program to do free sports physicals so the students could enroll in sports. The student body of the International High School in Langley Park in Maryland is 100% immigrants and refugees, most of whom are without insurance. “A sports physical costs $80-$100,” commented Dr. Milani as we drove to the school. In all, we saw about twenty students, about $2,000 in free services.

-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

-Ron Lapitan, Former Community Outreach Coordinator

Recent Comments